If it’s 4 p.m. on a Wednesday in Wilmington, that means Will Hart Park is hopping.

Cyclists and joggers sweat out laps around its perimeter. Parents lay blankets on the grass as kids tumble around. Adult men play pickup basketball; teenage boys and girls practice tricks off skate ramps next to the hoopsters.

But the biggest crowds are always outside the Wilmington Teen Center, on the north side of the park. The lines of people and cars aren’t there to use the nonprofit’s horseshoe pits or outdoor gym, or play a round of Ms. Pac-Man in a vintage arcade.

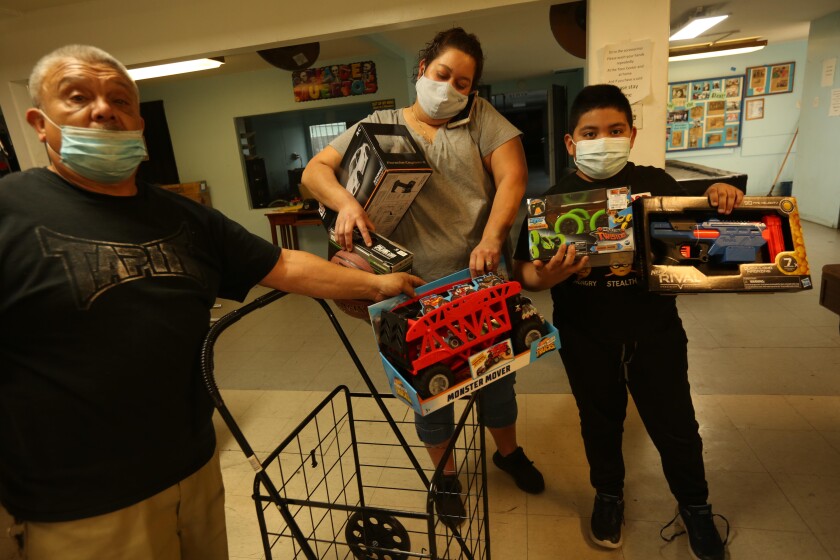

They wait for free food.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March, the Teen Center has had to curtail nearly all youth activities for the first time since it opened in 1968. It now functions more like a community pantry.

“Lots of parents are laid off now,” said Mike Herrera, a Wilmington native who’s the center’s director. He stood outside its front door on a recent Wednesday, next to a taped paper sign that read “Closed Due to Corona Outbreak.” Volunteers unloaded boxes of frozen chicken patties and loaves of bread, while women with foldable shopping carts chatted before the giveaway.

“I’ve got people with no jobs, no telephones,” Herrera, 68, added as I followed him inside the sprawling center for a tour. “The neighborhood is hurting, so we need to meet them where they’re at.”

Herrera has served as director for four years, with no salary. He took the Teen Center job after retiring as chief executive of the Boys & Girls Clubs of the South Bay because “I didn’t want to see this place close down. Doctors and lawyers and athletes have come from here.”

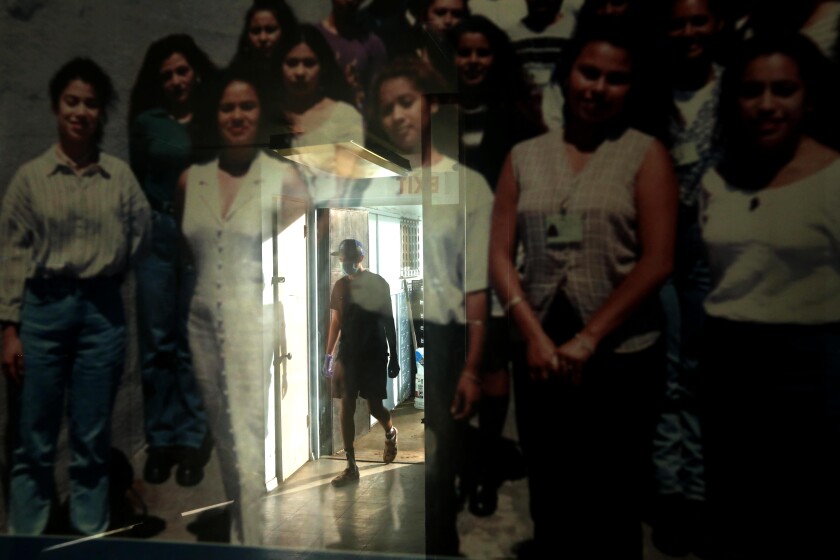

The Teen Center has seen better days. Footballs and basketballs sit unused on scuffed linoleum floors. Weeds choke up the parched soil of abandoned garden beds. A bulletin board with newspaper clippings from the storied space doesn’t seem to include anything newer than the mid-1980s.

“I just got a karaoke machine, but we can’t use it,” Herrera said as he turned on the lights in the computer lab, where monitors and desktops remain in their boxes. “It’s hard for me to look at everything, but we gotta keep pushing. That what Connie would’ve done.”

He’s referring to Connie Calderon, his former boss and the Teen Center’s longtime director. She was already a local legend when then-Rep. Glenn Anderson issued a proclamation from the House floor in 1975 that Calderon was “the heart of Wilmington.”

The short, tough daughter of Mexican immigrants was in the early years of a career that saw her welcome thousands of area children into the center’s well-worn rooms. Calderon connected her wards with job training at businesses or took them on field trips that their families could never dream of affording, like a Dodgers game.

Residents in the working-class town respected her so much that gang members declared the Teen Center neutral ground — don’t mess with it, or Calderon would get you with a well-deserved tongue lashing,

“I kick a lot of butt but I don’t box,” she told the Torrance Daily Breeze in 2008, upon news of her retirement. “The kids — when they’re young — they hate my guts because I’m hard on them. …They still come back.”

It was an early forced retirement: doctors had just diagnosed Calderon with Alzheimer’s. She finally passed away from the disease on Dec. 23. She was 81.

Her death hit me for two reasons. As someone who prides himself on knowing the hidden heroes and heroines of the Southern California story, I was ashamed I had never heard of Calderon.

But it was also a reminder that many similar nonprofits — often run on the pennies and perseverance of one person — are hurting right now. The pandemic has affected everyone, of course, but charities with big-pocketed donors will weather it. It’s smaller spots like the Teen Center, dedicated to helping out one neighborhood, whose struggles are particularly acute.

“We’re kinda lucky,” Herrera said as we finished the tour. “Other places like us have shut down altogether.”

Herrera first met Calderon as a student at Banning High School in the late 1960s. She had once studied to become a nun, but found her calling instead with neighborhood kids. As one of 13 children, she knew hard times but also the importance of helping those who need it.

“Connie would always say that she never knew a piece of steak bigger than a quarter, but at least she had a piece,” Herrera said. “Not everyone did.”

Calderon helped launch what was then called the Teen Post as part of a citywide youth initiative after the Watts riots. She spun it off into a nonprofit in the 1980s, and brokered a buck-a-year lease for the Teen Center’s building that continues to this day.

Regional boxing champs emerged from its musty ring. Youths got union jobs with only a high school diploma via summer apprenticeships arranged by Calderon, who never married or had children. People who went through the Teen Center’s doors credit Calderon with turning around their lives.

“She was always disciplining me,” said Ramiro Quezada, 58, as he lugged in packs of bottled water. “She wanted me to be a good person. And here I am doing what she always told us to do, help others.”

“It makes me full of joy to do this,” added Lorenzo “Mooney” Zepeda. The 59-year-old first met Calderon as a 14-year-old, when she gave him a summer job to help him recover after surviving a shooting in a case of mistaken identity. “Everything I learned, I learned from Connie.”

But the days when the Teen Center buzzed with activity are long gone. Herrera remembers when they could easily find 400 teens summer jobs at the Port of Los Angeles, thanks to a larger staff and Calderon’s connections. Today, he can afford to pay only three part-timers from a total annual budget of less than $100,000.

“People can’t give as much anymore,” he said. “Which is sad, because the kids and their parents from here need help more than ever.”

Herrera tries to see the positive as he contemplates the Teen Center’s present and future. The coronavirus, for instance, “was a blessing for free food.” Places that never wanted to donate, such as grocery markets and government agencies, now offer Herrera so much stuff that he can hand anyone two bags’ worth of items instead of just some canned vegetables like before.

And the hardship is inspiring others to take up the mantle of his mentor. Hundreds showed up for a car parade in July to let Calderon bask in Wilmington’s love one last time. Shortly after, 17-year-old Banning High senior Teresa Narvais got a job helping Herrera coordinate the food drives. She’s there almost every Wednesday to take down the names of attendees, and explains in English and Spanish that everything is free and comes with no catch.

Narvais had no idea who Calderon was before starting at the Teen Center. In a way, it didn’t matter: the teen has already absorbed Calderon’s most important lesson.

“Before, I wouldn’t like helping, but now I come here every day, even if I don’t get paid for it,” Narvais said as the grocery line grew. “There’s a lot of people who need help, and I see these families get happy when we do it. So do I.”

"center" - Google News

January 22, 2021 at 09:00PM

https://ift.tt/3sPBlAM

Column: A teen center turn into a food pantry to survive COVID-19 - Los Angeles Times

"center" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bUHym8

https://ift.tt/2zR6ugj

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Column: A teen center turn into a food pantry to survive COVID-19 - Los Angeles Times"

Post a Comment