Content warning: disordered eating

Did you know that eating disorders were the leading cause of mental health-related deaths until the opioid crisis? Or that members of the military are particularly vulnerable to disordered eating? Or that binge eating disorder has only been recognized as a formal diagnosis since 2013?

We’re willing to bet you didn’t—eating disorders, which affect nearly 30 million Americans, have long been misunderstood and underdiagnosed.

Not only is there a dearth of information surrounding these disorders, but they carry accompanying stigmas and misconceptions—but anyone can struggle with disordered eating, regardless of gender, body type, or socioeconomic status. That’s why Paula Quatromoni (SPH’01), a Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences associate professor and chair of health sciences, developed the new course Eating Disorders Treatment and Prevention. She wanted to cut through the fog and educate the next generation of registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs).

“I’ve wanted to teach this course for a long time,” Quatromoni says. “Eating disorders as a public health problem are underdiagnosed and undertreated and very little research dollars have gone to them relative to other health conditions, so they’re also under-resourced. All of that contributes to a stigma and barriers to accessing treatment.”

On the clinical side, training is often superficial, she says. “You don’t typically come out of a dietetics program with a competence to treat eating disorders—most people who work with eating disorder patients have to seek out additional training and certifications.

“We want to be part of the solution: we want to train future dietitians and prepare our students to be leaders in the field.”

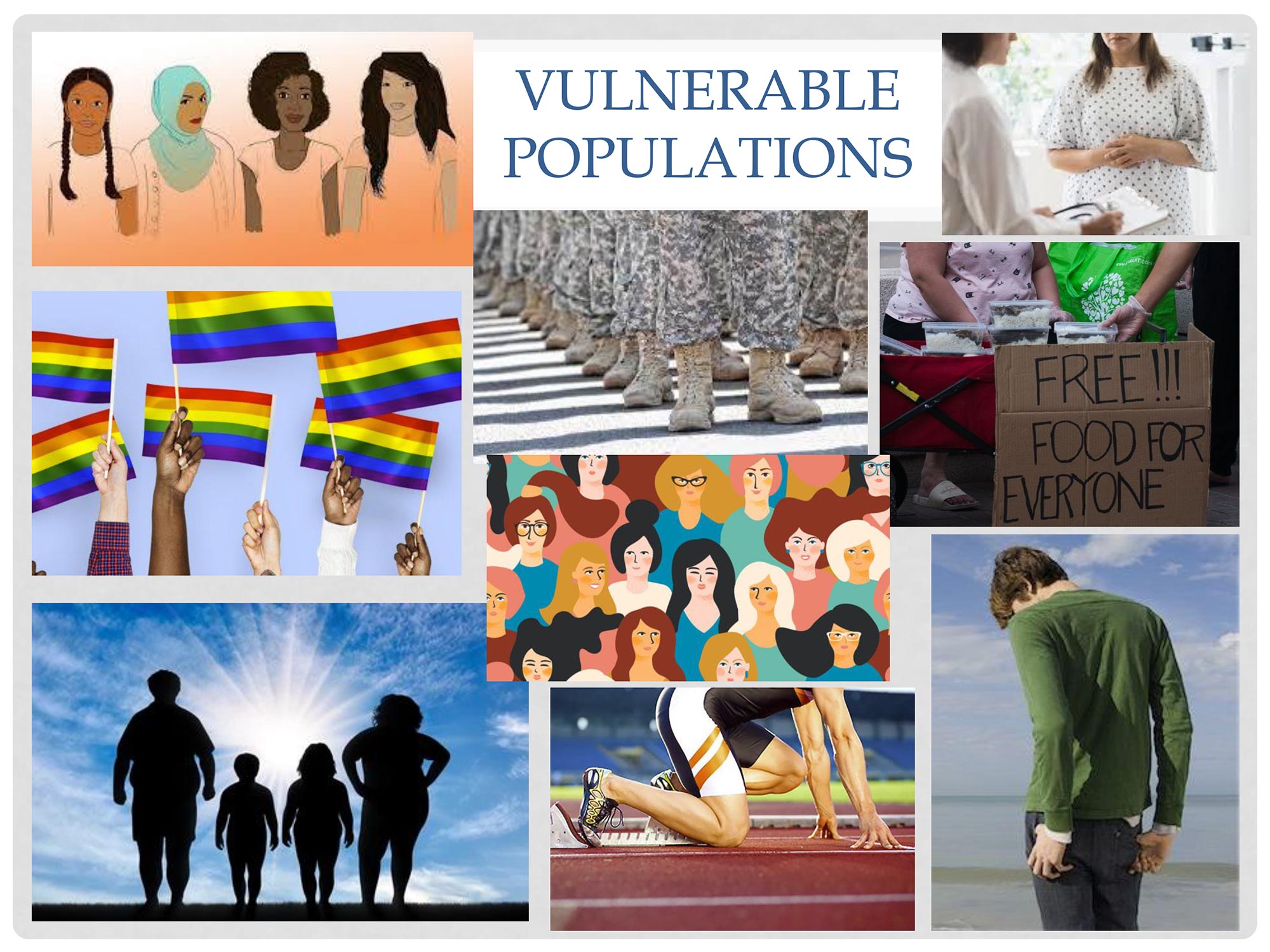

Eating Disorders Treatment and Prevention is a graduate-level elective also open to undergraduate seniors. Quatromoni has broken the course into two parts: impact and recovery. The first half covers diagnoses, signs, and the physical effects of malnutrition—bone-density loss, brain and muscle atrophying—as well as triggers, risk factors, vulnerable populations (which include men and the LGBTQ+ community), and misconceptions. “I told my students, ‘My job is to scare you,’” she says. “I want them to understand how the body breaks down, so they believe in their guts how essential and life-saving this work is.”

There’s this belief that it’s only rich white girls who have eating disorders—that it’s only perfectionist straight-A students with anorexia—but that’s a stereotype. Eating disorders don’t discriminate.

Presentation slide (left), from the new Sargent class Eating Disorders Treatment and Prevention. Slide courtesy of Quatromoni

The latter half of the course is on treatment methods for disordered eating. “It takes a lot of empathy,” Quatromoni says. There are different levels of treatment—inpatient, residential, partial hospitalization, intensive outpatient, private-practice outpatient—and she covers care at each level. Students learn tools like motivational interviewing, or uncovering what triggers a patient and what drives them to go into treatment, and food exposure, or gradually reintroducing foods a patient may have labelled as “bad” or triggering.

Quatromoni, a longtime RDN and researcher, has worked with eating disorders patients for years. The course sprang from her experiences treating young athletes at BU (which laid the groundwork for the sports-nutrition practices at Sargent Choice Nutrition Center and BU Athletics) and through her consulting work with Walden Behavioral Care treatment centers. As she tells her students, she’s seen every type of eating disorder, in every type of patient.

“There’s this belief that it’s only rich white girls who have eating disorders—that it’s only perfectionist straight-A students with anorexia—but that’s a stereotype. Eating disorders don’t discriminate,” Quatromoni says. “Food insecurity, for one, is a massive risk for disordered eating, specifically binge-eating and restrictive-eating disorders.

“My lab just finished up a study on people who have type 2 diabetes and binge-eating disorder—these are people who developed diabetes as adults, but guess what secretly developed a decade or more earlier? Binge-eating disorder, after years of experiencing body-shaming and weight-stigmatizing—from doctors! And I haven’t even talked about orthorexia [a fixation on clean-eating] yet.”

The course also highlights the lived experience of patients. One guest speaker is Ali Gold (Sargent’20), a former athlete and family friend of Quatromoni’s and a Nutrition Choice Center patient. Gold struggled with mental health throughout high school and developed multiple eating disorders and a compulsive exercise habit after deciding not to continue playing lacrosse in college. To her, speaking to the class is an important part of her recovery.

“It’s super therapeutic and meaningful for me to share,” says Gold, who spent her early 20s in and out of different treatment centers. “Doing advocacy work and talking to future professionals about my lived experience has been really instrumental to my recovery journey.

“In my experience, some people have been like, ‘Well, just eat,’ or ‘Just stop exercising,’” she relates. “And if it was that easy, I would have been doing that already. The fact is, [treating eating disorders] is so, so complicated. For professionals to be able to understand the science, and come at it with an empathetic, curious, trauma-informed approach—and have the right language to talk about it—is super important.”

She and Quatromoni also stress the need for more accessible treatment. Treatment is often ongoing and involves a variety of specialists (such as an RDN and a therapist, for starters). Many insurance companies offer coverage for eating-disorder treatment, but costs can add up fast—to say nothing of those who don’t have insurance at all. “A lot of statistics come from people who go into treatment,” Quatromoni told her students during an early March class. “And you know who goes into treatment? People who can afford it.”

A few weeks into the course, Quatromoni is already looking forward to future semesters. She’s constantly compiling resources for her students—right now, she recommends the documentary Gain, made by two patients who met in treatment—and she’s planning more clinical internships for dietetics students at Walden centers. In class, she speaks often about patients’ increased need for support during the COVID-19 lockdown, and the importance of empathy at every level of treatment.

“When you’re passionate about what you’re doing,” she says, “it’s very easy to teach.”

Are you or is someone you know struggling with disordered eating? Massachusetts resources include the Sargent Choice Nutrition Center and MEDA (Multi-Service Eating Disorders Association). Nationally, NEDA (National Eating Disorders Association) offers support groups, video series, and other remote resources during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Explore Related Topics:

"impact" - Google News

March 09, 2021 at 12:01PM

https://ift.tt/3rBd8xm

Sargent's New Course on Eating Disorders, from Impact to Recovery - BU Today

"impact" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2RIFll8

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Sargent's New Course on Eating Disorders, from Impact to Recovery - BU Today"

Post a Comment